This blog post originally appeared on Environmental Defence’s website.

Meeting the Canadians that Energy East puts at risk

It was a typical northern Ontario day on the shores of Shoal Lake, when I really got it.

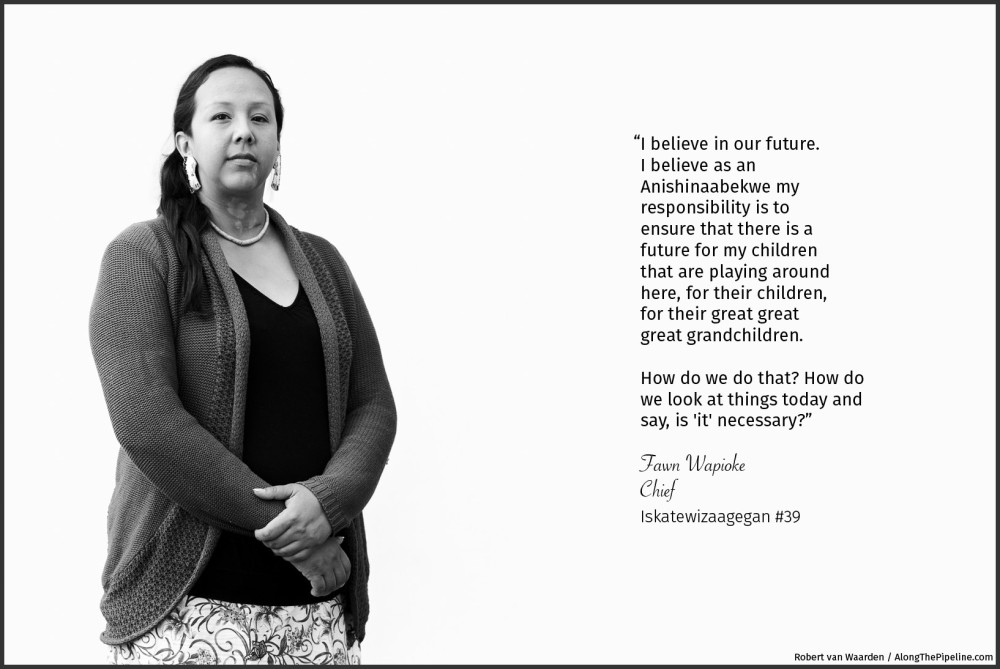

I was a month into a photography project to highlight the voices of people along the proposed Energy East pipeline route. I was interviewing Chief Fawn Wapioke of Shoal Lake 39. We had retreated from the mosquitos outside to a couch in the living room.

Fawn was talking about making decisions based on how they would affect future generations. I’d heard other individuals share similar sentiments before. But that day, Fawn’s toddler twins were playing at our feet. Listening to Fawn’s words and watching those kids play, it really sank in.

This was clearly about more than one pipeline. This was about building a different system – one where a clean environment and a sustainable economy provide a resilient system for future generations to thrive.

Last spring, I traced Energy East’s proposed 4,600 km route. All those kilometres provide a lot of stories, a lot of opinions and a lot of cups of coffee. This country we call Canada is a beautiful land full of beautiful people. Everywhere I went on my journey along the pipeline, people gave me hours and days of their time. They shared their life stories, homes, and food with a photographer determined to find out what Canadians and First Nations thought about plans for a massive new tar sands pipeline heading east.

Every individual had their own opinions informed by their own experiences. I talked to people that supported the pipeline, people still making up their mind and many that were doing everything they could to oppose it.

It’s clear that Canadians and First Nations are giving thought to the complex issues of energy, environment and economy. We are smart people. Many of us aren’t buying the line pushed by tar sands industry and the federal government that ‘we need this pipeline for jobs and the economy.’

Most also recognize the climate implications of the mega-pipeline. Every person I spoke with, whether they agreed with the pipeline proposal or not, talked about the need for Canada to move towards more renewable energy.

This is a complex issue. And, sometimes it takes a personal story, a face, or an experience to drive home what this is all about.

Beginning this Friday, some of the images from Along the Pipeline will be on display in Toronto for the exhibit Exposing Energy East. The exhibit is free and open to the public, October 31 to November 5.

I invite you to come and see the faces of Canadians who live along Energy East’s proposed route. Hear their concerns about this project. I promise it will make you consider not only the issue of the pipeline, but also ask that bigger question – what kind of Canada do we want to build?