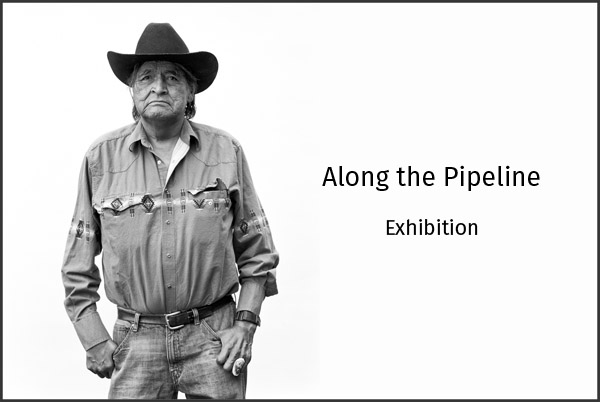

Sue and Andrew Clarke enjoy a cup of tea at their home near St. Briavels.

Once you get them started it can be hard to get them to stop. Talking about wind energy, Sue and Andrew Clarke bounce of each other, echoing or filling in the gaps when required. They love what they do and like everyone with a strong passion, they have sacrificed a lot to get where they are today.

Sue and Andrew live near St. Briavels in the Forest of Dean in western England. For 20 years they worked in large multinationals developing energy projects. When Sue started to work with the Transition Towns movement in her spare time they found their personal and professional lives diverging. During the week they could be found working on large energy projects and then on the weekend maybe marching in London for action on climate change.

They decided it was time to move on when a host of factors collided in 2008: economic downturn, support for renewables from the federal government, and Andrew’s professional life leading towards nuclear energy.

After many years of senior management in big business, they staked their pensions on wind energy and community owned development and founded Resilient Energy. They haven’t looked back.

“The best step that we have ever taken” says Andrew.

Sue and Andrew Clarke walking up the lane away from the St. Briavels wind turbine.

They devised a model for wind energy that will help meet, but not exceed, the energy needs of a community. This includes 50/50 joint venture ownership with the landowner with up to 70% of the revenue going back into the community. A key component of their model is crowd funding.

“With a feed in tariff you can get community projects off the ground, there is a guaranteed revenue stream from the government. There aren’t many businesses that you can get paid for 20 years for everything you generate. You can’t make pots and guarantee that someone is going to buy it,” says Andrew.

They worked with the crowd funding company Abundance and within four months had oversubscribed their St. Briavels turbine, raising a total of 1.6 million pounds. Over 450 people bought debentures with approximately 50% of them coming from the community. The youngest investor was 18 and the oldest was 82.

In a country that is known for it’s anti-wind lobbies, Sue and Andrew had a great experience the first time around. There were over 50 letters of support submitted from the community and only one against. However, their next couple of projects are stuck in planning. A well-organized anti-wind lobby is one reason, but ambiguity from the federal government is also a clear factor.

“We need a strong clear message from the government,” says Sue.

Dealing with the anti-wind lobby, Sue and Andrew have been forced to grow a thick skin. However, usually when they are really feeling low, the phone will ring from a stranger gushing enthusiastically about the St. Briavels turbine.

“Wind energy is a bit like marmite. No one goes around saying I love marmite, it is the best thing ever,” says Sue.

Sue and Andrew are particularly proud of the trickle down affect their work has had on their three sons. There were times when the money wasn’t readily available in the last few years because of their decision, but their sons have developed a greater understanding for this work and the issues. Their middle son is following in his parent’s footsteps and studying environmental science at university this year.

The Forest of Dean has a long history, it helped spark the industrial revolution and there is still coal to be found. There is a lot of energy in these hills and it seems that wind is the next logical step.

“Hopefully longer term it will get the communities thinking about what they actually need to be more resilient, thinking about the bigger picture,” says Sue.

The shadow of the St. Briavels wind turbine on the green pastures of St. Briavels.